Citation

Cross, F. B., & Tiller, E. H. (1998). Judicial partisanship and obedience to legal doctrine: Whistleblowing on the federal courts of appeals. Yale Law Journal, 107(7), 2155–2176. https://openyls.law.yale.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/e999df84-a83d-4db9-bb11-b46ba533e15a/content

Research Question

Under what conditions do U.S. courts of appeals judges, particularly on the D.C. Circuit, obey Supreme Court legal doctrine (Chevron deference) when that doctrine conflicts with their partisan policy preferences, and how does panel composition affect this obedience?

Key Takeaways

Chevron deference operates as a politically contingent tool rather than a neutral, automatic rule; ideologically unified panels are most likely to bend or sidestep Chevron when it conflicts with their policy goals; mixed panels show higher obedience to Chevron when a minority judge’s policy preference and the doctrine point in the same direction; both Democratic and Republican appointees use doctrine strategically, with no clear partisan asymmetry in legalism; internal ‘whistleblowing’ via potential dissent is a key mechanism through which doctrine constrains majorities on appellate panels.

Dataset Description

The authors studied all D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals decisions from 1991 to 1995 that substantively applied Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. NRDC’s deference framework. Using Shepard’s and Westlaw searches, they initially identified over 200 Chevron-citing opinions, then narrowed the sample to roughly 170 statutory interpretation cases in which Chevron’s two-step analysis was operative and outcome-relevant. Each decision was hand-coded for: (1) whether the court purported to apply Chevron and whether it deferred to the agency; (2) whether the agency decision was affirmed or reversed; (3) the ideological direction of the agency policy and of the court’s ultimate ruling (liberal vs. conservative, inferred from issue area, regulated entity, and challenger identity); and (4) the partisan appointment of each judge, producing measures of panel composition (unified Republican, unified Democratic, or mixed). The authors used cross-tabulations, chi-square tests, and logistic regression models to assess how panel ideology, ideological conflict within the panel, and the alignment between panel preferences and agency policy shaped Chevron deference and final outcomes during the 1991–1995 period within the federal D.C. Circuit.

Methodology

statistical/quantitative

Key Findings

The study finds that Chevron deference in the D.C. Circuit is not applied as a neutral, mechanical doctrine; it is systematically conditioned by panel ideology and internal panel dynamics. Panels are more likely to invoke and follow Chevron when the agency’s policy direction is ideologically congenial to the panel majority and markedly less likely to defer when Chevron would force a result contrary to the majority’s presumed policy preferences. Ideologically unified panels (all Democratic or all Republican appointees) display the greatest willingness to bypass or manipulate Chevron when doctrine conflicts with their preferred outcome, often by characterizing statutes as having ‘plain meaning’ or by deeming the agency’s interpretation unreasonable. By contrast, when panels are ideologically mixed (2–1), the presence of a minority judge whose policy preference aligns with what Chevron would require produces a ‘whistleblower’ effect: in such cases, the rate of doctrinal obedience is dramatically higher than on unified panels facing comparable conflicts, because the minority judge can credibly threaten to expose doctrinal manipulation through dissent. Both Republican- and Democratic-dominated panels engage in this strategic pattern, and the authors find no evidence that one party’s appointees are categorically more faithful to Supreme Court doctrine than the other. Overall, the results support a model of judicial behavior in which legal doctrine constrains but does not fully determine outcomes; instead, doctrine interacts with judges’ ideological preferences and the possibility of internal monitoring by ideological opponents to shape whether and how Chevron is applied.

Summary

Cross and Tiller’s article examines when federal courts of appeals, focusing on the D.C. Circuit, actually obey Supreme Court doctrine rather than selectively use it to advance preferred policy outcomes. Using Chevron deference as the test case, they merge doctrinal analysis with positive political theory and quantitative methods to ask a concrete behavioral question: under what conditions will judges follow Chevron when it pushes them toward an ideologically incongruent result?

The authors assemble a dataset of D.C. Circuit decisions from 1991–1995 that genuinely applied Chevron’s two-step framework in statutory interpretation disputes. They code whether the panel deferred to the agency, the ideological direction of the agency policy, and the resulting decision, and the partisan background of each judge, allowing them to distinguish unified (all Democratic or all Republican) from mixed panels. They then model how panel composition and the alignment between judges’ presumed policy preferences and the agency’s position affect the likelihood of Chevron deference and ultimate case outcomes.

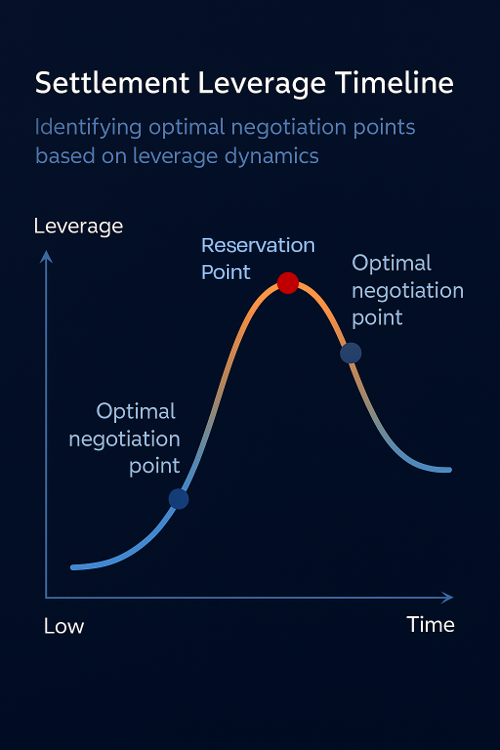

Empirically, they find that Chevron is followed more reliably when it supports the panel majority’s ideological direction and is frequently cabined or avoided when it would require an ideologically disfavored outcome. Ideologically unified panels display the lowest rates of obedience to Chevron in such conflict cases, suggesting that the absence of an internal critic makes doctrinal manipulation easier. However, when a panel is mixed, and a minority judge’s likely policy preference coincides with what Chevron would require, the majority’s propensity to obey Chevron rises sharply. The authors attribute this to a ‘whistleblower’ dynamic: the minority judge can credibly threaten to expose doctrinal inconsistency in a dissent, raising reputational and collegiality costs for the majority.

Thematically, the study shows that doctrine does matter, but as a constraint mediated by institutional context and ideological diversity. Legal rules like Chevron do not mechanically determine outcomes; instead, they interact with judges’ political preferences and the possibility of internal monitoring. For scholars, this supports an integrated model of judging in which attitudinal and legalist accounts are complementary rather than mutually exclusive. For practitioners, the findings underscore that panel composition, especially the presence of an ideologically opposed judge with clear doctrinal authority, can meaningfully alter both the likelihood of deference and the majority’s incentive to closely track Supreme Court doctrine.

How the Study Advances Empirical Understanding of Legal Outcomes

The study finds that appellate outcomes in Chevron cases exhibit structured, repeatable patterns shaped by institutional panel composition and the alignment between agency policy direction and panel-level ideological configuration, rather than by the neutral application of doctrine alone. The results indicate that legal doctrine functions as a contingent constraint within a decision-making environment in which internal monitoring mechanisms, such as the presence of an ideologically opposed panel member, systematically alter rates of doctrinal adherence across otherwise comparable cases. By relying on comprehensive case coding, panel composition analysis, and statistical testing across a defined body of appellate decisions, the study exemplifies the kind of empirical, case-based examination of legal outcomes and decision contexts that aligns with Pre/Dicta’s emphasis on rigorous structural analysis as a necessary component of high-level litigation practice.