Citation

Kastellec, J. P. (2007). Panel composition and judicial compliance on the U.S. Courts of Appeals. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 23(2), 421–441. Oxford University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40058185

Research Question

How does the ideological composition of three-judge panels on the U.S. Courts of Appeals affect those panels’ compliance with U.S. Supreme Court precedent?

Key Takeaways

Panel composition matters for compliance because individual judges act strategically, not as a unitary court; A single judge ideologically closer to the Supreme Court can constrain a majority by credibly threatening a whistleblower dissent; The size of the doctrinal “noncompliance zone” depends on dissent costs and how strongly the Supreme Court responds to dissents in certiorari; Many compliance effects are invisible because anticipated dissents never materialize once the majority moderates; Empirical studies must model facts, doctrine, and ideological distances to detect panel-composition effects on compliance.

Dataset Description

The study is primarily theoretical and does not build an original dataset. It develops a formal game-theoretic model of hierarchical interaction between the U.S. Supreme Court and three-judge panels on the U.S. Courts of Appeals, using search-and-seizure cases as the running example. Kastellec calibrates and interprets the model with reference to existing empirical studies of U.S. federal appellate decisions (including samples of Courts of Appeals cases from the late 20th century, such as D.C. Circuit administrative law decisions and post-1970s criminal procedure cases), but no new systematic coding of cases, judges, or outcomes over a defined time window or specific circuits is conducted. The empirical content is thus indirect: previously published datasets from U.S. federal appellate courts and Supreme Court review practices inform the plausibility and interpretation of the model’s parameters and comparative statics.

Methodology

Formal game-theoretic modeling; statistical/quantitative discussion of prior empirical work

Key Findings

Kastellec demonstrates that treating a three-judge court of appeals panel as a group of strategic individual judges, rather than a unitary actor, fundamentally changes how we understand compliance with Supreme Court precedent. In his model, a judge who is ideologically distant from the panel majority but closer to the Supreme Court can act as a potential “whistleblower”: by threatening to dissent, that judge can substantially increase the probability that the Supreme Court will grant certiorari and reverse a noncompliant panel decision. Because the prospect of a whistleblower dissent informs the Supreme Court and is costly for the majority, the majority often moderates its decision ex ante to avoid provoking dissent, leading to greater adherence to Supreme Court doctrine than panel preferences alone would predict. The size of the ‘noncompliance zone’, the set of cases in which a like-minded majority can deviate from Supreme Court precedent without triggering a credible dissent, shrinks when (1) at least one judge on the panel is reasonably aligned with the Supreme Court, (2) dissents are relatively inexpensive to write, and (3) the Supreme Court treats dissents as strong signals in its certiorari decisions. The model clarifies why some empirical studies find weak or inconsistent panel effects on compliance: simple ideological coding of outcomes into “liberal” or “conservative,” without situating cases along the underlying factual-doctrinal continuum and without measuring the ideological distances between each judge and the Supreme Court, obscures the whistleblowing mechanism. Kastellec’s analysis implies that the likelihood of overt dissent is not a good direct measure of constraint: much of the compliance-inducing effect of minority judges occurs off the published page, through anticipated but unrealized dissent threats that discipline the majority’s decision.

Summary

Kastellec’s article examines how the ideological composition of three-judge panels on the U.S. Courts of Appeals shapes their willingness to comply with U.S. Supreme Court precedent. Rather than treating an appellate panel as a single actor, he models it as three individual judges whose preferences may diverge from one another and from the Supreme Court. The central insight is that hierarchy and collegiality interact: the presence of a judge close to the Supreme Court can discipline a like-minded majority that would otherwise drift from binding doctrine.

The heart of the paper is a formal game-theoretic model of hierarchical judicial review, illustrated with search-and-seizure law. Cases are placed along a substantive continuum capturing how intrusive a search is, while both the Supreme Court and each appellate judge have ideal points on that continuum. A majority on a panel might prefer to decide a case in a way that departs from what the Supreme Court would likely do. However, a minority judge whose ideal point is closer to the Supreme Court’s can threaten to dissent if the majority strays too far. Because dissents are informative signals in the Supreme Court’s certiorari process, that threat raises the expected likelihood of review and reversal. Anticipating this, the majority often chooses a more moderate, precedent-consistent outcome that avoids provoking an actual dissent.

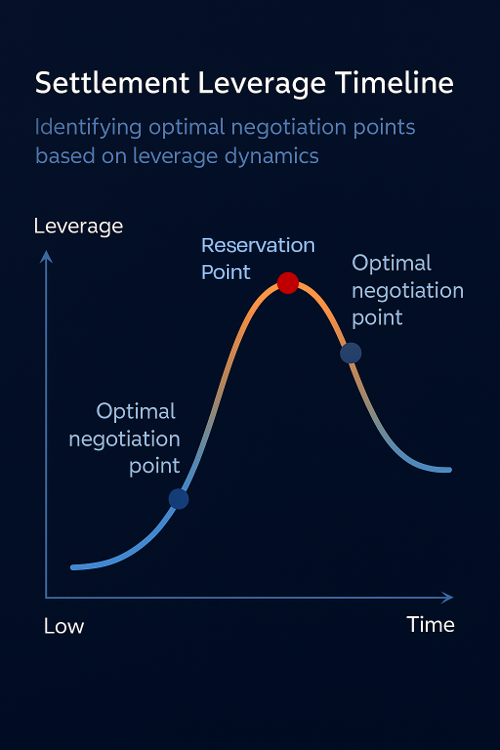

This logic produces a “noncompliance zone”: a range of cases within which a cohesive majority can quietly deviate from Supreme Court doctrine without triggering a credible whistleblower dissent. That zone shrinks when dissenting is relatively cheap for the minority judge, when the Supreme Court attaches high informational value to dissents in deciding whether to grant certiorari, and when at least one judge on the panel is ideologically proximate to the Court. In such situations, the majority’s incentive to comply is strong, even though the panel may appear unanimous on the surface. The absence of dissent does not signal the absence of conflict; rather, it often reflects the potential whistleblower’s success in disciplining the majority at the bargaining stage.

Kastellec then situates his model within the broader empirical literature on panel effects and compliance. He argues that many empirical null results arise because studies typically code outcomes as simply liberal or conservative and look at party-of-appointing-president effects, without embedding cases in the underlying factual-doctrinal space or measuring how each judge and the Supreme Court relate ideologically. His framework suggests that compliance and panel effects are most visible when researchers can approximate where cases fall along the relevant doctrinal dimension and estimate the ideological distances between panel members and the Supreme Court. Under that richer measurement strategy, one would expect to observe that mixed panels and panels including a judge close to the Supreme Court show narrower noncompliance zones than ideologically homogeneous panels far from the Court.

For appellate practitioners and court observers, the model offers a structured explanation for intuitive phenomena: why some panels, even with a strong ideological majority, still hew closely to Supreme Court doctrine; why many strategic disputes never surface as published dissents; and why the identity of the “outlier” judge on a panel can matter as much as the overall partisan balance. It underscores that hierarchical judicial behavior turns not only on broad ideological labels but also on the detailed configuration of judges’ preferences relative to the Supreme Court and on institutional features, dissent costs, and certiorari practices that determine how powerful a potential whistleblower can be.

How the Study Advances Empirical Understanding of Legal Outcomes

The study shows that appellate outcomes exhibit structured regularities generated by institutional hierarchy and collegial decision rules, demonstrating that compliance with Supreme Court precedent is shaped by panel configuration and anticipated review rather than random variation. By modeling appellate panels as collections of strategic actors operating within a hierarchical oversight system, the analysis explains how observable outcome patterns can arise even in the absence of dissent, highlighting the role of institutional incentives and informational signals embedded in appellate procedure. This methodological focus on formal structure, doctrinal space, and case-specific positioning aligns with Pre/Dicta’s emphasis on empirically grounded analysis of legal outcomes as products of decision environments rather than isolated judicial discretion.