Citation

Ash, E., & Chen, D. L. (2023). The pervasive influence of ideology at the federal circuit courts (NBER Working Paper No. 31509). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31509/w31509.pdf

Research Question

To what extent does the political party of the president who appointed federal circuit court judges predict outcomes across the full universe of federal courts of appeals cases, including non-salient disputes?

Key Takeaways

Ideological composition of appellate panels substantially shifts success probabilities for weaker litigants across most federal circuit cases; These ideological effects extend far beyond hot-button issues and appear strongly in routine and unpublished decisions; Democratic-appointed judges exhibit systematically lower deference to district courts in civil cases between seemingly equal parties, increasing reversal rates; Unanimous decisions still embed ideological differences, with 3–0 panels reaching different bottom lines depending on partisan composition; Ideological polarization in published appellate decisions has grown since around 2000, raising the strategic stakes of panel assignment.

Dataset Description

The study compiles a dataset of roughly 670,000 three-judge panel decisions from the U.S. federal courts of appeals (all regional circuits, excluding the Federal Circuit) from 1985–2020. Case information is drawn from PACER-style docket data and commercial legal databases (e.g., LexisNexis/Westlaw) and merged with the Federal Judicial Center’s Biographical Directory of Federal Judges to attach judge attributes (appointing president/party, gender, race, tenure). About 550,000 cases are classified into six “weak vs. strong” categories (criminal appeals, prisoner suits, immigration cases, civil cases pitting individuals/small entities against institutions, civil suits between private parties and the U.S. government, and original habeas/mandamus-type petitions). Approximately 80,000 additional civil appeals between seemingly equal private parties are analyzed separately. The dataset includes both published and unpublished opinions and spans multiple presidential administrations across all included circuits.

Methodology

statistical/quantitative

Key Findings

Using the appointing president’s party as an ideology proxy, the paper finds that panel composition systematically predicts outcomes in over 90% of federal circuit cases. In six large categories where one litigant appears weaker, panels with more Democratic appointees are markedly more likely to issue pro-weak outcomes: moving from an all-Republican to an all-Democratic panel increases the odds of a pro-weak result by roughly 55%. These effects are robust to circuit-by-year fixed effects, case-type controls, and judge demographics, and they persist in non-salient subject matter, in unpublished opinions, across criminal offense types, across circuits, and across presidential eras. The paper distinguishes a genuine pro-weak orientation from a generic pro-reversal tendency, showing that when the stronger party appeals, Democratic-leaning panels are less likely to reverse, implying that ideology affects which side wins rather than simply the likelihood of reversal. In civil cases between apparently equal private parties, Democratic-appointed judges are more likely to reverse or remand, consistent with lower deference to district courts. Even in unanimously decided published cases, the share of pro-weak outcomes varies significantly with panel composition, undermining claims that unanimity implies ideological neutrality. Finally, the ideology-outcome gap in published cases widens after roughly 2000, indicating growing polarization in the courts of appeals and an increasing influence of ideology on appellate outcomes.

Summary

This paper examines whether ideology, proxied by the appointing president’s party, shapes outcomes across the broad landscape of U.S. federal courts of appeals decisions, not just in high-profile, ideologically charged disputes. Using a vast dataset of about 670,000 three-judge panel decisions from 1985–2020, the author links panel composition to case outcomes across circuits and time, distinguishing cases where one side is plausibly weaker from those involving relatively equal private parties. The empirical strategy centers on how the share of Democratic versus Republican appointees on a panel predicts the likelihood that the weaker side prevails, while controlling for circuit-by-year fixed effects, case category, and judge characteristics.

The core finding is that panel ideology has a pervasive and quantitatively large effect. In six major categories where one litigant appears structurally weaker, criminal defendants, prisoners, immigrants, individuals or small entities facing institutions, private parties facing the federal government, and petitioners in habeas or similar original actions, panels with more Democratic-appointed judges are substantially more likely to rule for the weak party. Transitioning from an all-Republican to an all-Democratic panel increases the odds of a pro-weak outcome by roughly 55%. These effects remain when the author narrows the sample to non-salient case types, routine civil disputes, and unpublished decisions, demonstrating that ideology is not confined to headline-making issues but instead permeates the everyday work of the appellate courts.

The study also explores mechanisms and boundary conditions. It rejects the idea that Democratic appointees are simply more reversal-prone by showing that when the strong party is the appellant, Democratic-leaning panels are less likely to reverse. In a separate set of roughly 80,000 civil appeals between seemingly equal private parties, the pattern shifts: here, the key difference is in deference to district courts, with Democratic-appointed judges more likely to reverse or remand, suggesting a distinct ideological view about error correction versus finality. Unanimity, often cited as evidence that ideology plays little role, does not eliminate these dynamics; even in 3–0 decisions in published cases, the probability of a pro-weak outcome varies meaningfully depending on whether the panel is all-Republican, mixed, or all-Democratic.

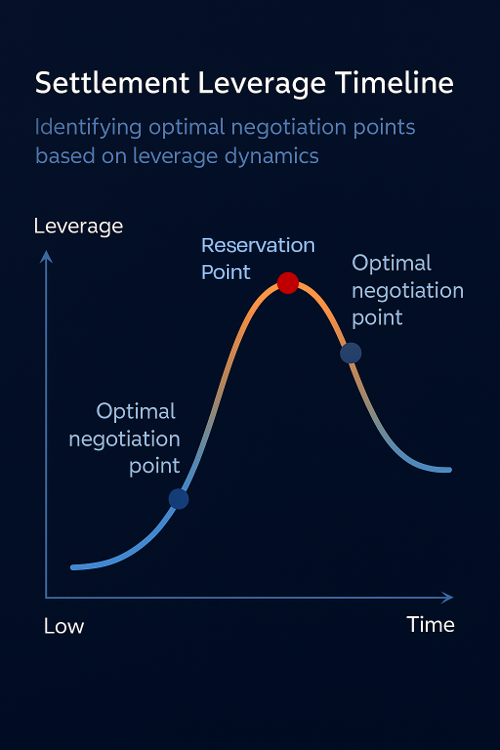

Over time, the study documents increasing polarization. Since around the late 1990s or early 2000s, the gap between Democratic- and Republican-appointed judges in their propensity to favor weaker parties in published cases has widened, consistent with a more ideologically sorted judiciary and a politicized selection process. For practitioners and scholars, these results imply that appellate outcomes are systematically influenced by judges’ ideological backgrounds in ways that are stable enough to be measured and predicted at scale. Legal merits and facts plainly matter, but the evidence shows that who sits on the panel materially shifts the odds, even in mundane cases, making judicial ideology an important input into litigation and settlement strategy.

How the Study Advances Empirical Understanding of Legal Outcomes

The study finds that appellate outcomes across the federal courts of appeals exhibit a systematic, repeatable structure rather than randomness, with decision patterns varying consistently with panel composition across a wide range of case types, including routine and unpublished matters. The results indicate that institutional features of the appellate process, such as panel-based decisionmaking, standards of review, and categories of litigant power, interact to produce stable outcome regularities that persist across circuits, time periods, and substantive domains. By relying on large-scale case data, explicit outcome coding, and controlled statistical analysis, the study exemplifies an empirical, case-based approach to understanding legal decision environments that aligns with Pre/Dicta’s emphasis on disciplined measurement of legal outcomes as a necessary foundation for high-level strategic litigation practice.