Citation

Edelman, L. B., Krieger, L. H., Eliason, S. R., Albiston, C. R., & Mellema, V. (2011). When Organizations Rule: Judicial Deference to Institutionalized Employment Structures. American Journal of Sociology, 117(3), 888–954. https://web.stanford.edu/~mldauber/workshop/Edelman.pdf

Research Question

How and under what conditions do federal judges come to treat organizational employment structures as evidence of compliance with anti-discrimination law, ultimately deferring to those structures regardless of their actual effectiveness?

Key Takeaways

Judges increasingly treat HR and compliance structures as evidence of legality, giving employers with sophisticated paper programs a credibility advantage; Deference to policies and procedures is strongest in disparate treatment cases, making it harder for plaintiffs to prove intent and easier for employers to win early; Government and public-interest plaintiffs face less judicial deference to employer structures than do individual, especially minority, employees; Challenging the adequacy and real-world use of policies is essential to rebut the default inference of compliance; Long-run trends in reference, relevance, and deference show judicial behavior is patterned and empirically measurable, not purely ad hoc.

Dataset Description

Quantitative content analysis of a random sample of 1,024 reported U.S. federal employment discrimination decisions (692 district court, 332 circuit court) from 1965–1999, drawn from Westlaw’s district and court of appeals databases. Cases involve Title VII, ADEA, Equal Pay Act, and §§ 1981 and 1983 employment discrimination claims (excluding ADA, Rehabilitation Act, and FMLA). Researchers coded 45 types of organizational structures (e.g., grievance procedures, anti-harassment policies, evaluation systems, discipline policies), case-level characteristics (parties, claims, theories, outcomes), and structure-level indicators of whether structures were referenced, treated as relevant, and deferred to. Advanced multivariate probit models were used to estimate trends and determinants of reference, relevance, and deference over time and across courts.

Methodology

statistical/quantitative

Key Findings

The authors show that federal judges increasingly use institutionalized employment structures as shorthand indicators of compliance, even though statutes do not require such structures and social-science evidence calls into question their effectiveness. Across 1965–1999, references to compliance structures (e.g., anti-discrimination policies, grievance procedures) and personnel systems (evaluations, progressive discipline, formal HR) rise, and courts become more likely to treat these structures as legally relevant and to defer to them without scrutinizing their quality. Deference emerges first in district courts and later in the circuits, and is strongest in disparate treatment cases where employer intent is hard to observe: the mere presence of policies or procedures becomes powerful circumstantial evidence of non-discrimination. Deference is least likely when plaintiffs are government or public-interest entities and more likely when plaintiffs are minorities or non-union individual employees, signaling that organizational form often trumps substantive fairness for weaker parties. Judicial ideology has surprisingly modest effects; both liberal and conservative judges absorb organizational “rational myths,” suggesting that patterned deference to institutionalized structures is a systemic feature of modern employment adjudication with direct consequences for whether discrimination claims survive and how employers structure their defenses.

Summary

This article develops and tests a theory of “legal endogeneity” in the context of employment discrimination. The central claim is that organizational structures such as grievance procedures, anti-harassment policies, performance evaluations, and progressive discipline systems become widely accepted symbols of rationality and compliance inside firms, and those same symbols migrate into the courts. Faced with ambiguous statutory standards and difficult questions about discriminatory intent, judges progressively treat the mere existence of such structures as evidence of legality, often without investigating whether they are effective in practice.

The authors conceptualize legal endogeneity as unfolding in three stages: reference, relevance, and deference. Reference occurs when judicial opinions simply mention organizational structures; relevance when courts treat those structures as probative of liability or non-liability; and deference when judges infer compliance from the presence of structures with little scrutiny of their adequacy. Using a random sample of 1,024 federal district and circuit employment discrimination decisions from 1965–1999, coded for 45 types of organizational structures and multiple case characteristics, the authors estimate multivariate models to track how each stage evolves over time and across case types.

Empirically, they find that references to both compliance structures (e.g., anti-discrimination policies, reporting systems) and personnel systems (e.g., performance evaluations, formal discipline, HR departments) increase steadily across the period. Courts are more likely to treat these structures as relevant to outcomes and, most importantly, to defer to them, especially in disparate treatment cases where intent is central but hard to observe. Deference appears first in district courts and diffuses to the courts of appeals, suggesting a bottom-up institutionalization of organizational forms within legal reasoning. In harassment and hostile work environment cases, where Supreme Court precedent emphasizes effectiveness, judges are somewhat less willing to treat policies as conclusive, but still tend to credit formal structures.

The distribution of deference is not even across parties. Government and public interest plaintiffs receive less judicial deference to employer structures than individual plaintiffs, particularly minority and non-union workers, who are more likely to face courts that treat organizational form as a proxy for substantive fairness. Ideological differences among judges play only a modest role; both liberal and conservative judges appear to absorb organizational “rational myths” about HR systems and due process. The authors conclude that legal endogeneity is a systemic feature of modern employment adjudication: organizational structures, once institutionalized in the business field, reshape the content and application of discrimination law by guiding what evidence judges see as credible and what counts as compliance.

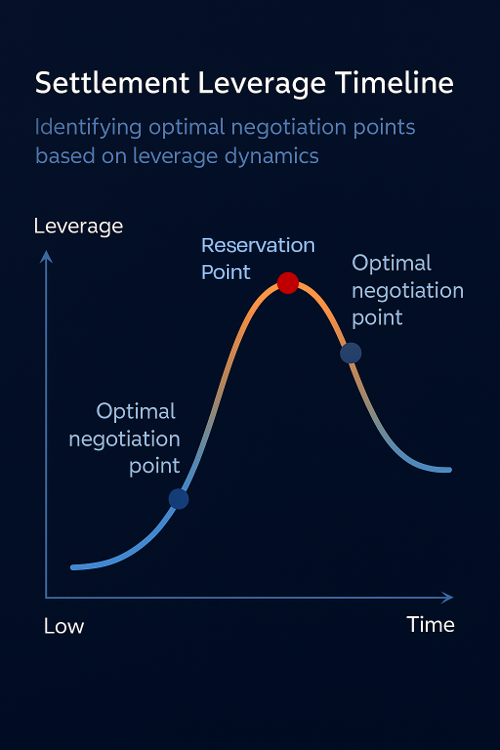

For practitioners, the study underscores that internal HR and compliance architectures are not neutral background facts but central evidentiary tools. Employers benefit from building highly visible, standardized structures that map onto judicial expectations of rational governance. Plaintiffs, by contrast, must transform those same structures from taken-for-granted markers of good faith into contested empirical objects by probing accessibility, usage patterns, and disparate impacts. The article ultimately shows that judicial decision-making is patterned and measurable rather than idiosyncratic, and that understanding courts’ growing deference to institutionalized structures is essential for any strategic approach to employment discrimination litigation.

How the Study Advances Empirical Understanding of Legal Outcomes

The study finds that legal outcomes in employment discrimination cases exhibit a measurable pattern of legal endogeneity, in which federal judges progressively treat organizational employment structures as symbolic evidence of compliance with anti-discrimination law. The results indicate that judicial behavior follows a patterned transition from merely referencing HR structures to treating them as legally relevant and ultimately deferring to them as proxies for non-discriminatory intent, particularly within disparate treatment decision environments. This analysis shows that the study’s methodology, which tracks the institutionalization of organizational forms within judicial reasoning, is consistent with Pre/Dicta’s emphasis on empirical, case-based analysis of decision contexts as a necessary and qualified component of strategic litigation practice at a high level.