Citation

Rao, M. (2020). Whither justice? Judicial capacity constraints worsen trial and litigant outcomes. University of California, San Diego. https://manaswinirao.com/files/whitherjustice_manaswinirao.pdf

Research Question

How do trial court judicial vacancies in India affect the duration and outcomes of civil trials and the economic performance of litigating firms, particularly plaintiffs?

Key Takeaways

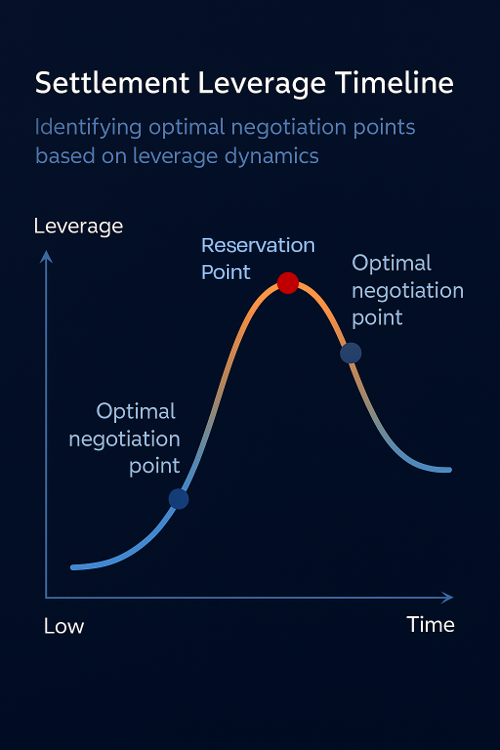

Judicial vacancies in Indian trial courts measurably lengthen cases and increase dismissals without adding process, creating hidden timing and termination risk; Plaintiffs are hit far harder than defendants, with higher dismissal rates and subsequent drops in wages and assets, so initiating suit in vacancy-prone courts is economically hazardous for smaller firms; The exogenous, rotational nature of judge transfers produces patterned shocks that can be anticipated and priced into litigation strategy, forum choice, and settlement advice; Capacity constraints operate like a structural bias in favor of non-complaining parties, reinforcing the need to understand individual courts’ vacancy histories and backlogs before committing to litigation; Empirical tracking of judicial capacity and vacancy exposure is a practical tool for counsel to manage duration risk, dismissal risk, and business impacts for clients.

Dataset Description

The study uses (1) the universe of 6.96 million unique civil trials in 1,967 courtrooms across 195 Indian district courts from 2010 to 2018, drawn from the national e-courts metadata (including filing and resolution dates, case type, litigant names, and basic outcome stamps); and (2) an annual panel of formal-sector firms from CMIE Prowess, focusing on non-banking firms with at least one ongoing case in the trial sample (5,236 matched firms, 91 trials on average, median 2). Trials and firms are fuzzy-matched via litigant names. Judicial vacancy is coded at courtroom-year level, and firm-level exposure is defined as having any ongoing case in a court experiencing vacancy in a given year. Identification exploits variation across trials within the same courtroom and court-year, with courtroom, court-year, and case-type fixed effects, and firm and year fixed effects for firm outcomes.

Methodology

statistical/quantitative

Key Findings

Using plausibly exogenous timing of judicial vacancies created by India’s centralized, periodic transfer system, the paper shows that when an ongoing trial is hit by a vacancy, its duration increases by about 168 days (0.3 SD) without any compensating change in the number of hearings, suggesting pure delay rather than additional process. Such cases are substantially more likely to go uncontested and to be dismissed by the successor judge. For matched firm litigants, the pattern is sharply asymmetric: when a firm appears as plaintiff, vacancy roughly doubles the dismissal probability and is followed by 7–12 percent reductions in legal spending, wage bill, and asset value; when the same firms are defendants, effects are smaller and statistically indistinguishable from zero. Because smaller firms disproportionately appear as plaintiffs, these capacity-driven delays and dismissals function as a structural bias that shifts risk and cost onto weaker parties, with direct implications for how counsel should think about forum exposure, timing risk, and the value of early resolution in capacity-constrained courts.

Summary

This paper examines a form of “bias” in the civil justice system that does not come from ideology or identity, but from institutional capacity: vacant judgeships in India’s district trial courts. Leveraging detailed court-level metadata and firm-level financials, the author asks what happens to cases, and to the businesses behind them, when an ongoing matter is abruptly left without a judge.

The empirical design exploits India’s structured but capacity-strapped assignment system. Judges are rotated annually across district courts, with transfers typically announced statewide on a common calendar. Because there are chronically fewer judges than sanctioned courtroom slots, transfers create long-lived vacancies that affect all ongoing matters in that courtroom. By comparing cases within the same courtroom and court-year that do or do not straddle a vacancy, and absorbing courtroom, court-year, and case-type fixed effects, the paper treats vacancy timing as a quasi-random shock. Event-study checks show no meaningful pre-trends in filings or resolutions by litigant type, supporting a causal interpretation.

On the trial side, the results are stark. When a case encounters a vacancy, its duration increases by about five to six months, yet the total number of hearings does not rise, indicating postponement rather than more process. These cases are about 15 percentage points more likely to go uncontested and significantly more likely to be dismissed by the successor judge without full trial. When attention is restricted to cases involving matched formal-sector firms, the patterns are similar but magnified: dismissal rates increase by roughly 15 percentage points overall, and by more than 20 points when the firm appears as plaintiff, while defendant-side cases see no comparable jump.

The paper then follows the vacancy shock into firms’ financial statements. Defining a firm-year as “treated” if any of the firm’s ongoing cases experiences a vacancy, and using firm and year fixed effects, the author shows that plaintiff firms exposed to judicial vacancy subsequently cut legal expenditures, wage bills, and asset values by roughly 7–12 percent. Sales and accounting profit do not move significantly, suggesting firms absorb shocks by shrinking their workforce and balance sheet rather than immediately altering revenue streams. For firms exposed as defendants, point estimates have the same sign but are about half the magnitude and statistically insignificant.

For litigators and policymakers, the message is that judicial capacity constraints are not background noise. They are systematic, measurable, and tilt the playing field in predictable ways. Vacancy risk lengthens timelines, increases the probability that a plaintiff’s suit is dismissed without merits resolution, and translates into real economic contraction for smaller, plaintiff-side firms. This creates asymmetric stakes in delay: defendants can often ride out vacancies, while plaintiffs face heightened risk that their claims die on the vine. Strategically, this raises the value of careful forum selection, of monitoring vacancy and transfer calendars, and of using early motion practice and settlement to mitigate exposure in chronically understaffed courts.

How the Study Advances Empirical Understanding of Legal Outcomes

The study finds that legal outcomes exhibit measurable structure through institutional capacity constraints, demonstrating that judicial vacancies in Indian trial courts lengthen case durations by approximately 168 days and significantly increase the probability of dismissal without additional hearings. The results indicate that these capacity-driven shocks are sharply asymmetric, doubling dismissal probabilities for plaintiff firms while leaving defendant outcomes statistically unchanged, thereby creating a structural decision environment that favors non-complaining parties. This methodology shows that empirical, case-based analysis of individual court backlogs and vacancy histories is consistent with Pre/Dicta’s approach and serves as a qualified and necessary component for litigation partners to manage timing and termination risk in strategic practice.