Citation

Engstrom, D. F. (2013). The Twiqbal puzzle and empirical study of civil procedure. Stanford Law Review, 65(6), 1203–1248.

Research Question

What do existing empirical studies of Twombly and Iqbal actually show about the impact of heightened pleading standards on federal civil litigation, and how should empirical methods in civil procedure be improved going forward?

Key Takeaways

Headline Twiqbal statistics often reflect weak sampling, citation-based searches, and coarse coding decisions rather than true shifts in judicial hostility; The most methodologically careful studies find only modest increases in Rule 12(b)(6) grant rates for cases that actually draw motions post‑Twiqbal; Whether a dismissal order truly removes a plaintiff from court—versus trimming claims or granting leave to amend—is central but was overlooked in many early studies; Selection effects, chilled filings, and strategic motion practice meaningfully mediate Twiqbal’s effects and cannot be ignored in access‑to‑justice debates; PACER-based, party-level, statistically controlled analyses are essential for reliable pleading-risk assessment, forum choice, and settlement strategy under Twiqbal.

Dataset Description

The article is a methodological and synthetic review rather than a single new dataset. Engstrom canvasses roughly twenty empirical studies of Rule 12(b)(6) practice before and after Bell Atlantic v. Twombly (2007) and Ashcroft v. Iqbal (2009). The underlying studies draw on Westlaw and Lexis samples of published district court opinions; PACER-derived near-censuses of Rule 12(b)(6) motions in 23 federal districts (Federal Judicial Center studies); and specialized datasets focused on particular case types, including employment and housing discrimination, civil rights, ADA, and financial instrument litigation. The temporal coverage runs from the late Conley era through the immediate post-Iqbal years (roughly the mid‑2000s through about 2010) in U.S. federal district courts, with some studies extending slightly beyond.

Methodology

Statistical/quantitative, doctrinal, mixed methods (systematic review of empirical studies).

Key Findings

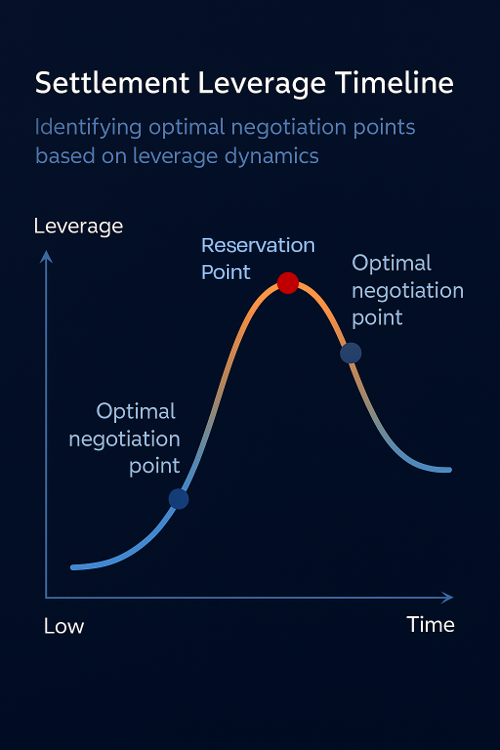

Engstrom demonstrates that widely cited statistics about Twombly and Iqbal’s supposed revolution in pleading are highly contingent on research design. Early studies that rely on Westlaw or Lexis, use citation-based searches, and code at the opinion or claim level—without distinguishing between partial and terminating dismissals or between with- and without-prejudice rulings—tend to show large post‑Twiqbal increases in dismissal rates. Many also fail to control for changes in case mix, district differences, or motion practice, and they do not track whether plaintiffs successfully amend and continue litigating. In contrast, more rigorous work drawing on PACER near‑censuses, multivariate models, party-level outcomes, and better coding of leave-to-amend status generally finds only modest, single‑digit increases in grant rates for cases that actually face Rule 12(b)(6) motions. When Gelbach’s selection-effect framework is layered on top of these results, Twiqbal’s impact appears to operate significantly through off‑the‑record channels: chilled filings, changes in which cases defendants choose to move against, and shifting settlement dynamics in the shadow of perceived stricter pleading standards. Engstrom concludes that Twiqbal has nontrivial implications for access to justice, but its effects are more nuanced than early “Twiqbal killed civil rights” narratives suggest. He argues that credible assessment of procedural reforms requires PACER-based, party-focused, and design‑sensitive empirical methods that account for selection effects and distinguish trimming from truly case‑terminating outcomes.

Summary

Engstrom’s article interrogates the rapidly growing empirical literature on Twombly and Iqbal to ask what we really know about their impact on federal civil litigation. Rather than offering a new dataset, he conducts a systematic methodological critique of roughly twenty existing empirical studies that examine Rule 12(b)(6) practice before and after the Supreme Court’s shift to plausibility pleading. His goal is both descriptive—clarifying Twiqbal’s true effects—and methodological—improving empirical civil‑procedure scholarship.

He shows that much of the early literature rests on fragile foundations. Many studies use Westlaw or Lexis samples keyed to citations of Conley, Twombly, or Iqbal, thereby overrepresenting published, often more salient, decisions and underrepresenting routine, unpublished docket activity. Coding is frequently done at the opinion or claim level, with little distinction between orders that terminate a case and those that merely prune claims or grant leave to amend. Few studies control for case type, district, or temporal shifts in the composition of the docket, and very few track what happens after a dismissal with leave—whether plaintiffs replead successfully or quietly exit. These choices systematically inflate the apparent magnitude of Twiqbal’s impact.

Engstrom contrasts these early efforts with more sophisticated work that leverages PACER data, near‑census samples, multivariate regression, and party-level outcome measures. Federal Judicial Center studies and research by scholars such as Gelbach and Boyd find that, once these design improvements are adopted, the jump in dismissal rates among cases that actually face Rule 12(b)(6) motions is modest—often on the order of a few percentage points. Yet when selection effects are modeled explicitly, it becomes clear that Twiqbal can still meaningfully affect access to justice: some plaintiffs never file, some cases settle differently, and defendants calibrate their motion practice in anticipation of more receptive courts, even if published grant rates do not explode.

On this basis, the article argues that debates about procedural reform must move beyond raw counts of dismissal grants in published opinions. For litigators and policymakers, the relevant questions are who sues, what kinds of claims are being filtered out pre‑filing, how specific judges and districts handle leave to amend, and what fraction of plaintiffs successfully replead. Engstrom frames this as part of a broader research agenda, calling for both fine‑grained hypothesis testing and large‑scale mapping projects that chart how different groups and claim types fare in the federal civil system. He ultimately positions Twiqbal as a case study in how procedural doctrine, litigant behavior, and empirical method interact—and how careful, data‑driven analysis is needed to understand and guide that interaction.